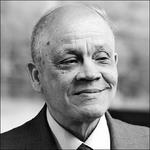

To those who knew him, Fritz Daguillard was a man driven by curiosity. He reveled in the culture of his native Haiti, loved studying its history and also collected artwork that viewed the accomplishments of Black people through the eyes of European artists.

But the doctor, who died of covid-19 at Suburban Hospital on Nov. 30, 2020, could point with equal pride to a remarkable career in medical research. He was 85.

In the 1970s, Daguillard founded one of the first schools in the field of immunology at Laval University in Quebec and served on the Canadian Medical Research Council.

Later, at the Hôpital des Enfants-Malades in Paris, the world’s oldest pediatric hospital, he studied severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), the genetic condition that causes children to live as “bubble babies” in a plastic-cocooned, germ-free environment.

“He was proudest of his work on the T cell; he was one of the first researchers to identify its involvement in immune response,” said his wife, Rita. “He also organized one of the earliest leukocyte conferences in 1972 at La Malbaie in Quebec.”

His work with UNESCO and the World Health Organization in the 1980s took Daguillard to sub-Saharan Africa at the height of the AIDS epidemic. He continued his study of HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, when he came to the District in 1985 to lead the AIDS evaluation clinic for the D.C. Department of Health.

In the last two decades, after his retirement from medicine, Daguillard zealously focused on historical research and art collecting, teaching a course on the Haitian Revolution at Benedict College in Columbia, S.C., and serving on the Committee for the Celebration of the Haitian Revolution.

His collections formed the basis of three art exhibits sponsored by the Haitian Embassy, one on the abolitionist Sen. Charles Sumner of Massachusetts and his efforts to gain U.S. diplomatic recognition for Haiti; a bicentennial celebration of the Haitian Revolution; and “Enigmatic in his Glory,” an exploration of the frequently contradictory likenesses of revolution leader Toussaint L’Ouverture in artwork. Daguillard returned several times to his native land to lecture on L’Ouverture and the Haitian revolution and even used his medical background to explore the controversies surrounding the Haitian liberator’s death and autopsy.

“He expressed pride that he was a medical professional who had interests outside his work,” his son Robert said.

Daguillard began acquiring sketches, prints and paintings in the 1960s, but the avocation really took hold during a Paris sabbatical. By the 1980s he had cultivated innumerable relationships in the Parisian art world, not only with galleries and dealers but often with the artists themselves.

French informalist painter and sculptor Jean Messagier gifted him a sketch of civil rights icon Angela Davis. He purchased several portraits of renowned American jazz musicians by Polish painter and poster artist Waldemar Swierzy and later commissioned a portrait of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. from Swierzy.

Fritz Daguillard was born June 1, 1935, in Les Cayes, Haiti. His father owned an import-export business. He received a medical degree from the University of Haiti in Port-au-Prince and came to the United States in 1963 for a residency at Albert Einstein Hospital in Philadelphia. He received a master’s from Harvard Medical School and, after moving to Canada, a PhD from McGill University in Montreal.

Daguillard and wife Rita, an attorney who has retired from the U.S. Transportation Department, were married for 53 years and lived in Bethesda.

John Lawrence, a retired curator with the Historic New Orleans Collection, worked with Daguillard on an exhibit about the Haitian migration to Louisiana before the Louisiana Purchase. He recalled how devoted the doctor was to chronicling the story of his people.

“He was always a student,” Lawrence said. “He never stopped learning.”

“That’s what makes a good collector,” he added. “You’re never at the point where you know it all. It’s having a great eye and a sharp mind and passionate pursuit for the material coupled with a willingness to share it — the ability not only to present these things but to tell the story and also state where the objects drive the narrative.”

![Phyllisia Ross – KONSA [Official Music Video]](https://haitiville.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/phyliisia.jpg)