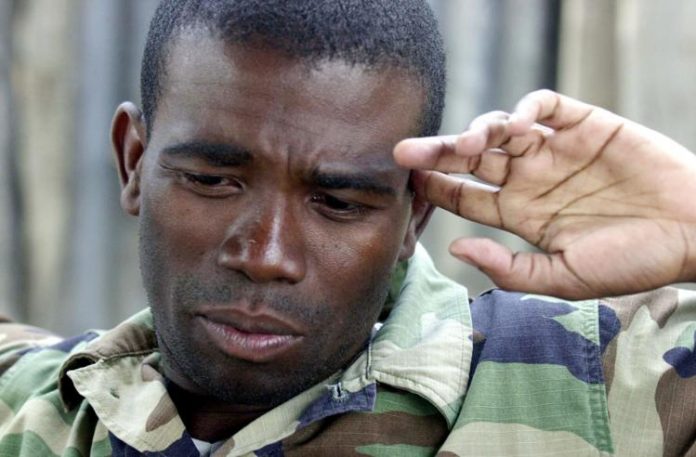

MIAMI — Guy Philippe is a man of many moves.

The former Haitian police commander once led a government rebellion against a president. He was later elected to a seat in the Haitian Senate just before being captured by U.S. authorities who had hunted him down for nearly a dozen years for pocketing more than a $1 million from Colombian cocaine traffickers.

Philippe cut a plea deal with federal prosecutors in Miami, but even then he still tried several times to get his nine-year sentence reduced while representing himself both before and during the pandemic era.

Now, the 55-year-old is scheduled to be released Thursday from a federal prison in Atlanta, transferred to U.S. immigration custody and eventually deported to Haiti, a country reeling from the July 2021 assassination of its president, Jovenel Moïse, and the terror of deepening gang violence since Philippe’s arrest more than four years earlier.

His possible return to Haiti as the United States is trying to stabilize the security situation is fueling concerns about how his presence back in the country might affect an already volatile landscape.

A State Department spokesperson did not want to discuss Philippe’s return to Haiti and directed questions about his deportation to the Department of Homeland Security.

“Mr. Philippe was lawfully arrested by the Haitian authorities and legally extradited to the United States,” the spokesperson said.

Nevertheless, Philippe’s pending return to his volatile homeland is raising questions about U.S. policy regarding Haiti and even has former U.S. diplomats who served in the country and are aware of Philippe’s controversial reputation baffled.

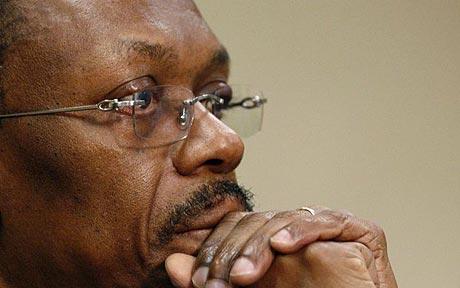

“I’m not close enough to the situation to comment on the facts, but this does seem a particularly bad time to add gasoline to a raging fire,” said Jim Foley, a retired diplomat who served as U.S. ambassador to Haiti between 2003 and 2005, during which time Philippe led a bloody coup against the then-sitting president, Jean Bertrand Aristide.

Luis Moreno, who overlapped with Foley and served as deputy chief of mission in Port-au-Prince from 2001 to 2004, said given how perilous the security situation currently is in Haiti, “it’s incomprehensible how anyone could think this was a good idea. Maybe there is something I don’ t know about.”

“He still has influence. He still has guns. He still has access to narco-trafficking,” Moreno said. “He also has intense political aspirations and ambitions. He wants to be the ruler of Haiti, he wants to be the dictator of Haiti. It has always been his dream and his objective. And that’s dangerous.”

Ahead of his release, Philippe filed a petition with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, requesting precautionary measures based on what he says is “a history of persecutions he had previously faced in Haiti and the fear of future harassment; threats and irreparable harm, on account of his political opinions and expressions.”

“Mr. Philippe is petitioning the Commission to actively appeal to the Government of Haiti to provide him with adequate security to protect his rights to life and personal integrity; to adopt the necessary measures so that he can carry out his activities without being subjected to acts of violence, intimidations, threats, or any harassments in the exercise of his daily life,” the petition, obtained by the Miami Herald, said.

Philippe who has passed the time in federal prison by releasing voice notes from prison about his case, refers to his Jan. 5, 2017, arrest by Haitian police as a “kidnapping” and his extradition to the United States on that same day as “illegal” and “politically motivated.”

The seven-member commission, an autonomous organ of the Organization of American States, has not yet ruled on Philippe’s request, stating that it requested information from Haiti on Nov. 17, 2022 but has received no response to date.

Philippe’s next move is anyone’s guess, but in court papers filed last year he expressed “his commitment to return to society as a law-abiding citizen” and “participate in the betterment of his community in Pestel, Haiti,” in the western region of the country.

“He had a vocal group of followers, many of whom are probably waiting for his return to Haiti,” said David Weinstein, a former assistant U.S. attorney who is now a Miami defense attorney. He led a team of prosecutors that brought indictments against Philippe and more than a dozen other Haitian police officers, politicians and business people on drug-trafficking and related money-laundering charges nearly two decades ago.

“The situation in Haiti today is even more fragile than when he was expelled in 2017,” said Weinstein, the former chief of the narcotics section at the U.S. attorney’s office. “The potential remains for him to mobilize his followers and return to a position of power in Haiti.”

Whether Philippe, who refers to himself as a senator, can run for office again in Haiti will depend on the yet-to-be-written electoral law and whether it continues its ban of individuals who have been convicted of crimes.

Philippe’s U.S. conviction

In April of 2017, Philippe pleaded guilty to a money laundering conspiracy charge, allowing him to avoid going to trial on a more serious trafficking charge that could have sent him to prison for the rest of his life. Instead, he faced up to 20 years on the money laundering conviction and got less than half that time from U.S. District Judge Cecilia Altonaga in line with a joint recommendation by prosecutors and defense lawyers.

The sentencing culminated a federal investigation into drug trafficking, money laundering and corruption at the highest levels of Haiti’s government that began in the 2000s when the island of Hispaniola, which Haiti shares with the neighboring Dominican Republic, became a notorious hub for shipping South American cocaine into the United States. For years, Aristide, who was ousted in 2004 in an armed revolt led by Philippe, had been investigated by a Miami federal grand jury for accepting drug bribes. Charges were never filed.

Philippe’s punishment was the result of a deal that became inevitable after Altonaga refused to dismiss the case based on Philippe’s claim of immunity as a senator-elect in Haiti. She also chastised the federal government for not trying harder to arrest Philippe since his 2005 indictment. He was arrested by the Haiti National Police and turned over to the Drug Enforcement Administration in early January 2017, days before his swearing-in.

The timing of his arrest in Haiti allowed the then-government of interim President Jocelerme Privert to govern the country without the looming presence of Philippe, who had threatened to divide the country shortly before Privert came into office. A supporter of Jovenel Moïse, Philippe openly campaigned with him before Moïse became president in 2017. Moïse would name the head of Philippe’s political party, Jeantel Joseph, to an important security post.

In Miami, federal prosecutors agreed to the lower end of the sentencing guidelines — ranging from nine to 11 years — for Philippe’s punishment because they believed the amount of time was in line with other Haitian officials who had pleaded guilty to similar money laundering offenses. They cited two defendants: former national police chief Jean Nesly Lucien and former presidential security chief Oriel Jean.

Lucien was sentenced in 2005 to almost five years after admitting he received $180,000 in drug proceeds as bribes. He did not cooperate with authorities.

Jean, bodyguard for Aristide, was sentenced in 2005 to three years in prison after helping the U.S. attorney’s office as a cooperating witness to convict several Haitians and Colombians of moving tons of Colombian cocaine through Haiti to the United States. He admitted receiving $400,000 in bribes. Jean, who testified in the only Miami trial that ended with the conviction and life sentence of a Haitian drug trafficker, was gunned down a decade later in Haiti’s capital. His assassination remains unsolved.

The U.S. government’s cases were built largely on cooperating witnesses involved in drug trafficking or protection in Haiti. In those cases, prosecutors relied mostly on witnesses and bank accounts rather than seizures of cocaine. The prosecutions of Haitian officials were challenging because the illegal activity happened in an impoverished foreign country where police officers were often on the take and tracing bribes was difficult. Also significant, the cocaine loads shipped from Colombia to makeshift airstrips in Haiti were long gone by the time U.S. investigators uncovered the trafficking through the island.

Philippe’s case was all the more difficult because he had been on the lam for almost 12 years while cultivating a Robin Hood reputation in the western reaches of the country far from the capital. For more than a decade, federal agents, in collaboration with the Haiti National Police, made at least 10 attempts to arrest Philippe: setting up checkpoints, paying informants, launching a U.S. military operation and pursuing him in a foot chase, only to lose him in dense vegetation.

In U.S. custody, Philippe admitted accepting at least $1.5 million in cocaine profits from Colombian traffickers between 1999 and 2003. According to a statement filed with his plea deal, Philippe admitted that he not only shared the bribes from narco-traffickers with fellow officers in the Haiti National Police, but he also wired hundreds of thousands of dollars to the United States to buy a home in Broward County, Florida, and support his U.S.-citizen wife.

Pierre Esperance, a human rights defender in Haiti, said Philippe has been issuing threats from prison, trying to intimidate individuals as he singles them out in recordings that have been shared on social media.

“Guy Philippe is someone who has been judged and condemned for drug trafficking in the United States,” said Esperance, the head of the National Human Rights Defense Network in Port-au-Prince. “I am hoping he is a changed man and has taken a lesson from his incarceration and will rehabilitate himself so he doesn’t continue with the threats, intimidations and what he was previously involved with.

“Even if it’s true that there are problems in Haiti, it is not a savanna that he is returning to,” Esperance said. “And if he continues doing what he was doing before, then his place is in prison.”

Philippe was the last high-profile defendant from a U.S. crackdown on cocaine smuggling through Haiti that yielded the convictions of more than a dozen drug traffickers, Haitian senior police officers and a former Haitian senator. Among them: Beaudouin “Jacques” Ketant, a Haitian narco-trafficker who accused Aristide of turning a blind eye to the cocaine. Ketant, initially sentenced to 27 years in a U.S. prison, was deported to Haiti in 2015 when his term was cut in half after assisting federal prosecutors in their probe.

![Phyllisia Ross – KONSA [Official Music Video]](https://haitiville.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/phyliisia.jpg)