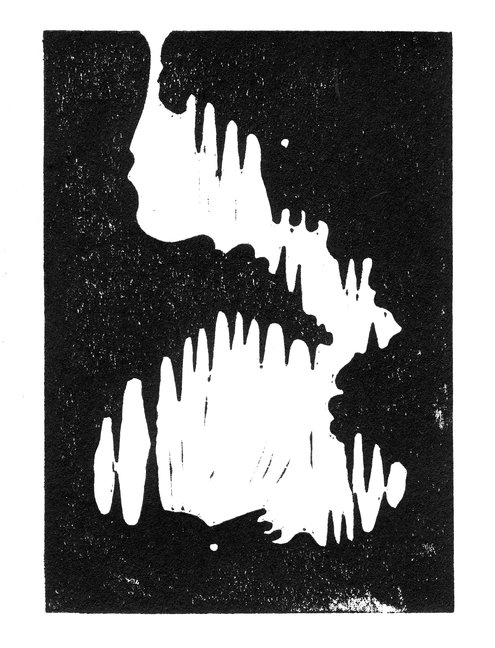

She is dreaming of caves and the rocks and minerals with which he’s obsessed. In the dream, he tells her that touching one of the columns rising from the cave floor could cause the stalagmite to die. She laughs and tells him that this might be one reason people no longer live in caves. He corrects her and says: “Maybe not in Brooklyn, but some people elsewhere do. Forced by weather, maybe during or after hurricanes, or during a war. Hiding, or for protection.”

He reminds her that there are breathtaking — though he’d no longer use that particular word — enviably beautiful, he might say, million-year-old caves he would love to see, caves with mile-long pits, canyons and shafts, even waterfalls, and with explosions of colors from marble arches, selenite crystals, ice pearls or glowworms, caves that are so striking they could burn your pupils with their beauty.

He can no longer speak this way, his body vibrating with each word, his fists raised in exhilaration, his head bouncing from side to side, as though he’s always trying to generate a room’s worth of enthusiasm for the high school juniors and seniors to whom he teaches earth and environmental science. At home, his sentences had grown short and clipped even before he became visibly ill. He was beginning to sound like some of her newly arrived cousins, curtly speaking a borrowed tongue, while the language they’ve been hearing since birth slowly slipped away.

This summer, they were planning to visit the grottos and caves of their parents’ birthplace, near the town where her mother was born, in the south of Haiti.

“One of the caves is your namesake,” he said when they decided to solicit honeymoon funds for the trip on their wedding registry.

The cave had, like her, been named for a nurse and soldier, Marie-Jeanne Lamartiniére, who dressed as a man to fight alongside her husband against the French colonial army during the Haitian Revolution.

“Who would I have to dress as to be able to see you, and fight for you, with you?” she asks him now. “Would I have to be a doctor, or a chaplain? Are you — the atheist — even allowed a chaplain, just in case you wake up and demand conversion?”

A recollection of his racing breath jolts her awake. What scares her most now, in this recent hierarchy of terrors, is not his silence, or the gasping beats of the ventilator, which is hours old, but when the shift changes and someone speaks into the phone that had been placed next to his ear. The exhausted female voice on the other end, a voice she imagines as a mezzo-soprano in an a cappella group, from the way her intonation rises and falls so quickly and dramatically — that voice purposely perks up and says: “Good morning. Am I speaking to the love of Ray’s life?”

How did you know? she wants to ask. Of course they take notes, on iPads or notepads, for one another to read, small details to differentiate, individualize. The night nurse might have been able to make out her words after all. He might have written down exactly what Marie-Jeanne had bawled and blubbered through: “His name is Raymond, but we call him Ray. He is the love of my life.”

“What did you two spend the night talking about?” the morning nurse asks. And before reminding her to recharge the phone so she can speak in his ear again, later that morning, and maybe in the afternoon, and perhaps again tonight, Marie-Jeanne sleepily answers in her scratchy, mostly bass voice: “Caves. We were talking caves.”

They didn’t always talk about caves. During their four-month courtship, between the new science teachers’ orientation and their New Year’s Eve wedding in the Flatbush Avenue restaurant owned by his parents, they talked more generally of travel. This was one advantage of their profession after all, their great fortune in having the summers to check off bucket-list items. He liked to describe their planned trips as though they’d already happened. He wanted them to ride a steam train between the river gorges of Zambia’s Lower Zambezi National Park and Victoria Falls Bridge, and hoped that before they had children they would climb Machu Picchu, swim with penguins in the Galápagos, gaze at the northern lights from inside a glass igloo. But first they had to go on the delayed honeymoon to her namesake cave.

As soon as she hangs up with the nurse, she imagines driving to the hospital and circling the main building. She’d park under the sweet gum tree by the front gate. In ordinary times, this street would be a conduit to a lobby where visitors sign in before finding their way inside the hospital maze. The day before, she dropped him off on the other side of that building, at the emergency-admission section. Two people in what looked like spacesuits had wheeled him inside. He could still breathe on his own then and was even able to turn his head and wave in her direction. It was not a goodbye wave.

The day before, she dropped him off on the other side of that building, at the emergency-admission section. Two people in what looked like spacesuits had wheeled him inside. He could still breathe on his own then and was even able to turn his head and wave in her direction. It was not a goodbye wave. Go on now, he seemed to be saying under the face mask, his nightshade eyes obscured by fogging aviator glasses. There is a long line of people behind you.

She wonders now where in the hospital he might be, what floor, what room. The night nurse won’t say, perhaps so she and others don’t storm the building and rush to those floors to hold their loved ones’ hands. The nurse simply says that they were taking good care of him.

“I know,” she said, much in the way he might have. “I know you’re doing the best you can.”

She thinks that tonight on the phone she will play some of his favorite Nina Simone again. Last night she played “Wild Is the Wind” 16 times — for the 16 weeks they’ve been married. At their wedding, everyone was expecting some kind of gag, a hip-hop interlude in the middle of their first dance and his abysmal break dancing interrupting the mournful jazz, but they danced the entire seven minutes of the live recording, cheek to cheek. You kiss me. With your kiss my life begins. You’re spring to me. All things to me. Don’t you know you’re life itself?

She could call back and ask the nurses to play the song for him right now, but the ward might be too busy during the day. Both words and melody might be muffled by the stream of hurried movements and rush to beeping machines. In any case, the night is when relief might be most needed from both his and her nightmares.

She doesn’t realize that she’s nodded off until the phone rings and in one swift movement she grabs it from the folds of the yellow duvet on their bed, while wiping the sleep from her eyes. She can hear the Creole news broadcast blasting from the radio that’s always on in her parents’ apartment as they thank her for the groceries she’s had delivered to them. When they ask how her husband is doing, she says, “Same.”

When his parents call, she asks if they want her to add them to her call to him later on that night. They could tell him stories, folk tales or family anecdotes, remind him of things he’d loved and treasured when he was a boy.

“Give him a reason to come back to us,” his mother summarizes what Marie-Jeanne is struggling to say.

“It’s not fully up to him, is it?” his father interrupts. He sounds distant, as though speaking from another extension, in another room, rather than on speaker on his wife’s cellphone.

“I know he wants to come back to us,” her mother-in-law says. “We’re praying all the time. I know he will.”

There’s a funeral that maybe she can help them watch online, the father says, a service for good friends who have “fallen.” He says “fallen” in such a literal way that Marie-Jeanne at first thinks his friends have slipped in the tub or on the stairs.

“We were sent a link and a password,” her mother-in-law says. She sends the link and password to Marie-Jeanne via text, along with the instructions, and somehow Marie-Jeanne manages to talk them through joining the private funeral group on their laptop. Before she hangs up, Marie-Jeanne hears her mother-in-law ask her husband, “Are you sure you can watch?”

Marie-Jeanne uses the link to connect to the service. The camera seems to be recording from a corner of the funeral home chapel’s ceiling. It’s a double funeral, a couple, married 45 years, who died three days apart. They’d been at her wedding. They contributed $200 to the honeymoon funds. They are among the oldest friends of her in-laws. The couple’s three daughters, their husbands and four of their oldest grandchildren are sitting on chairs arranged on what looks like every other square of a giant chessboard. The two coffins are draped with identical velvet purple palls. Marie-Jeanne swipes the screen before hearing a word.

Her namesake cave is three miles long and more than a million years old. The first chamber, with the ecru-colored floor, is two stories high, he’d said. Farther in, there are chambers with stalactites shaped like the Virgin Mary and wedding cakes. Inside one of the cave’s deepest and darkest chambers, which explorers have named the Abyss, you can hear echoes of your own beating heart.

Tonight she might retell him everything he’d told her about the caves. She would remind him too of how when she seemed hesitant to “plunge in” so soon after they’d met, he asked her to pick one thing about him to focus on at a time, one thing that could make her forget everything else. Today that thing is the caves. Tomorrow it might be Nina Simone. Again. The next day, it might be the bobbing of his head when he was talking about something he loved, or how she could predict his next move by looking past the nerdy glasses and into his eyes.

The phone rings once more, and her arm instinctively reaches for it before she realizes what she’s doing. The same nurse who was trying to sound so upbeat a little while ago is now carefully parsing her words.

“I intended to mention this earlier,” the nurse says. “There are a few words meant for you on your husband’s admission file. I don’t know if they were shared with you.”

Waiting for some graver pronouncement to follow, Marie-Jeanne answers “no” in such a low voice that she has to repeat the word.

“Would you like me to read them to you?” the nurse asks.

Marie-Jeanne pauses, purposely stretching the time, so if there was some other news, she might delay it for a while. Whatever the words are, she does not want to hear them in a stranger’s voice. That much she knows. She wants to hear herself reading them, or better yet, she wants to hear him saying them.

“I can email you a screenshot,” the nurse says. “Someone’s already taken a picture.”

“Please,” Marie-Jeanne answers.

When the email alert pops up on her cellphone, she knows even before she reads the words what they will be. Ray had written on a plain white piece of paper: MJ, Wild Is the Wind.

The words look as though they’d been scribbled, in a hurried cursive, with a trembling hand. “MJ” is written in a straight line, but the rest of the words glide down the paper, degenerating, in shape and size, to the point that she’s not a hundred percent sure that the last word is not “Wing.”

She remembers him once telling her that inside the Marie-Jeanne cave, sounds carry weight and travel in waves strong enough to possibly crack some of the most fragile karst. She imagines herself standing at the lowest depths of this cave, in the Abyss, and hearing again what he whispered in her ear during their wedding dance. One thing, MJ. This is our one thing.

![Phyllisia Ross – KONSA [Official Music Video]](https://haitiville.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/phyliisia.jpg)