The year the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) came to the country was a deadly one for my family. In February of 2004, Haiti’s first democratically elected President, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, was forced out of office for a second time, having been reinstated, and then reëlected, after a 1991 military coup. This time, Aristide was replaced by Gérard Latortue, a former United Nations official, who called those who took up arms against Aristide “freedom fighters.” (Their leader, Guy Philippe, is serving a nine-year sentence in a U.S. prison after pleading guilty to receiving multimillion-dollar bribes from cocaine traffickers.)

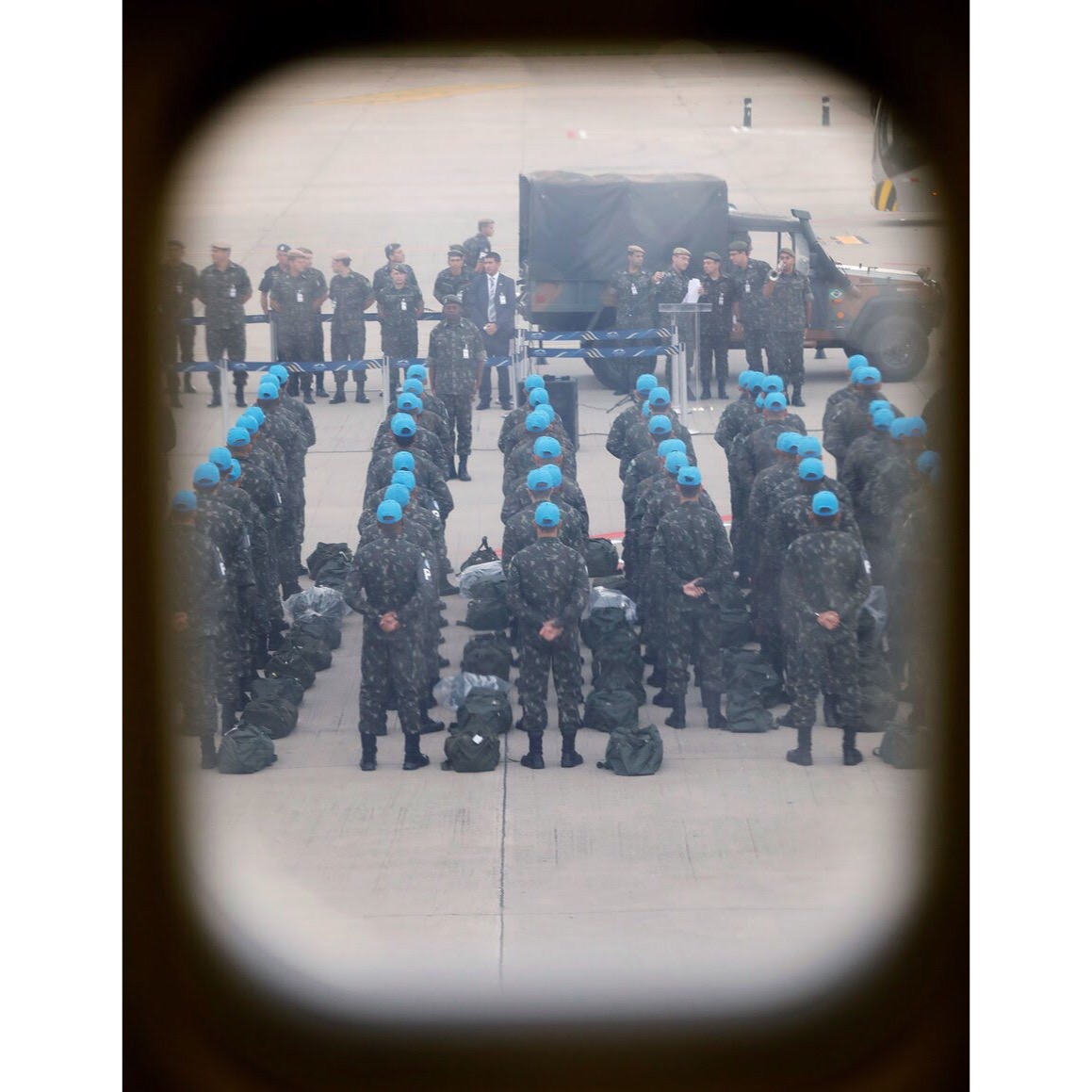

That April, claiming that the situation in Haiti constituted “a threat to international peace and security in the region,” the U.N. Security Council passed Resolution 1542, establishing the Brazil-led MINUSTAH. The mission, which officially began in June, 2004, lasted thirteen years and five months, and cost more than seven billion dollars, before officially ending this past Sunday.

Part of MINUSTAH’s mandate was to assist the transitional government in insuring “a secure and stable environment.” This is where my loved ones and others came into the mission’s crosshairs.

I spent the first twelve years of my life in an impoverished neighborhood in Port-au-Prince called Bel Air, where many Aristide supporters live. My eighty-one-year-old uncle, a minister, had called this neighborhood home since the nineteen-fifties, and was there on September 30, 2004, when protests began on the thirteenth anniversary of the first coup d’état. In response, the Haitian national police and MINUSTAH soldiers conducted joint raids in Bel Air that led to dozens of mostly unreported injuries and deaths. The following month, U.N. soldiers and Haitian riot police climbed up to the roof of my uncle’s church and killed some of his neighbors below. My uncle was forced to flee to Miami, where he died in the custody of U.S. immigration officials after being denied asylum.

Bel Air was not the only area subjected to these raids. During one of their bloodiest operations in Cité Soleil, another poor and densely populated neighborhood in the capital, MINUSTAH used more than twenty-two thousand bullets and seventy-eight grenades, among other artillery, to kill seven alleged gang members. No other deaths were acknowledged despite further raids until early 2007, when the mission head at the time, Edmond Mulet, brushed off such killings as collateral damage. This combat terminology was not incidental. MINUSTAH was a continuous military operation in a country in which there was no war.

There would be more collateral damage. In October, 2010, nine months after an 7.0-magnitude earthquake nearly flattened Port-au-Prince and the surrounding areas and killed more than three hundred thousand people, and while more than a million people were still displaced or living in makeshift tent camps, Nepalese peacekeepers stationed in the north of Haiti allowed raw sewage from their base to leak into one of Haiti’s largest and most intensively used rivers, causing a cholera epidemic. The U.N. at first refused to investigate the source of the outbreak and instead blamed Haiti’s lack of sewerage and water-treatment facilities. More than ten thousand people have died from cholera since 2010, and more than eight hundred thousand have been infected.

It took the U.N. six years to acknowledge its role in the cholera epidemic, and even though the former Secretary-General, Ban Ki-moon, declared last December that the U.N. needed to “do the right thing”, the U.N. continues to reject victims’ legal claims by citing immunity. The U.N. has also failed to deliver on Ban’s promise of a four-hundred-million-dollar fund to halt the spread of cholera and compensate the “most affected” victims. The fund has only raised $2.7 million, and the current U.N. Secretary General, António Guterres, seems unwilling to provide direct payments to the cholera victims and their families, many of whom have lost their sole breadwinner.

Neither the U.N.’s impunity nor the lack of accountability would surprise the women and boys and girls, many as young as twelve, who have told of being raped—one boy says that he was gang-raped—by MINUSTAH peacekeepers, who, according to the Associated Press, have used sex rings, offers of food, and other methods to trap their victims. Unacknowledged “MINUSTAH babies” and their destitute mothers are treated as though they do not exist. Though MINUSTAH rapes remain underreported, those who have come forward have had to confront the same type of repudiation faced by the initial cholera victims. Their rapists were rarely punished. They were simply sent home.

MINUSTAH has now been replaced by MINUJUSTH, a smaller mission which began on Monday. MINUJUSTH , the United Nations Mission for Justice Support in Haiti, has a mandate to “help the Government of Haiti strengthen rule-of-law institutions, further develop and support the Haitian National Police and engage in human rights monitoring, reporting and analysis.” MINUJUSTH, which will will consist of twelve hundred and seventy-five officers and support personnel, seems like a rebranding effort, an attempt by the U.N. to give itself a clean slate and erase MINUSTAH’s past. But if the U.N. were serious about justice and human rights in Haiti, it would wind down its presence in the country by having MINUJUSTH also investigate the damage done to both individuals and entire communities by MINUSTAH. Or, better yet, assign an independent body to do so, then offer the warranted compensation for the extrajudicial and civilian killings, the sexual assaults, and the introduction of cholera.

Haiti’s current President, Jovenel Moïse, whose two heavily contested election cycles are often touted as a MINUSTAH success, told the Miami Herald in an interview this month that “the conversion of MINUSTAH to MINUJUSTH is the recognition of the progress made by our country in recent years. Today, Haiti is no threat to regional and global peace and security.” To fill in the gap being left by MINUSTAH, Moïse plans to revive the defunct Haitian Army, whose history of human-rights abuses, the coup d’état against Aristide, in 1991, and its subsequent reign of terror led to an earlier United Nations mission, UNMIH, in 1993.

Moïse’s proposed budget for 2017, which calls for new tariffs and increased taxes on goods and services, has been a subject of mounting protests in Haiti. MINUJUSTH, like its predecessors, will likely find itself facing angry Haitians, or training those who do. Why should Haitians trust another group of U.N. “peacekeepers” who claim to promote the same human rights, justice, and rule of law that have been so blatantly violated by their colleagues? The U.N. may want to leave MINUSTAH’s dark chapter behind, but Haitians will have to suffer the consequences of the group’s actions for generations to come. And no new mission, under whatever acronym, will change that.

Edwidge Danticat is the author of many books, including, most recently, “The Art of Death: Writing the Final Story.”

By: Edwidge Danticat, The New Yorker | October 19, 2017

![Phyllisia Ross – KONSA [Official Music Video]](https://haitiville.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/phyliisia.jpg)