Travelling by boat, bus and on foot, treacherous journey from Brazil ends at Roxham Road, Que.

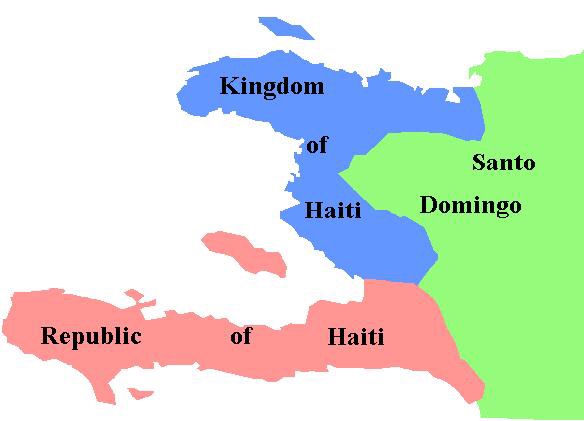

When Pierre left Cap-Haïtien for South America, he never imagined he’d wind up in the woods of upstate New York.

But nine years and 10 countries later, he stepped into Canada and was arrested by the RCMP.

He had survived a two-and-a-half-month, 15,000-kilometre odyssey from Brazil to Roxham Road with his wife and seven-year-old son, through some of the most dangerous territory in the Americas.

By plane, by boat, by bus, taxi or on foot, the destination was always the same: “Anywhere but Haiti.”

Pierre is not his real name. CBC News has agreed to protect the identities of the 30-year-old Haitian and his family to prevent any potential impact on their asylum claim in Canada.

Building a life in Chavez’s Venezuela

A self-described socialist, Pierre left Haiti in 2008 to study in Venezuela. He made a new life for himself in Hugo Chavez’s Venezuela, where he worked as a warehouse manager.

Pierre left Haiti to study music in Venezuela in 2008, later studying accounting and administration. (submitted by Pierre)

When the revolutionary president died in 2013, Pierre went south to Manaus in the Brazilian state of Amazonas.

But work dried up, so in 2016 he decided to head north to “conquer the American dream.”

It’s a path countless others have taken — a backwoods channel for waves of undocumented Latin Americans, Africans, South Asians, Haitians and Cubans seeking a better future.

It’s also a route fraught with exhaustion, fear, robbery, rape and death.

Desperate journey through the Darien Gap

With his wife and child, Pierre set out on June 16, 2016, crossing into Venezuela from Brazil.

“It wasn’t easy to get into Colombia, but with a lot of tenacity we managed,” he said.

From there the family boarded a bus to the Colombian port town of Turbo, where the South American stretch of the Pan-American Highway ends.

There they joined a group of 100 or so other migrants – Cubans, Africans and other Haitians ready to make the same desperate journey.

“From Turbo, we took a little boat,” Pierre recalls. “Many people died because some boats sank. But we arrived at the entrance to the Darien Gap.”

The Darien Gap is a lush rainforest on the border of Colombia and Panama, thus named because it’s a break in the Pan-American highway.

Migrants must travel through the untamed wilderness on foot.

“Crossing the Darien Gap was a very cruel experience,” says Pierre. “I spent six days in the mountains with no food and no water.”

“So as not to get dehydrated, my family and I had to drink our own urine.”

The migrants also had to avoid snakes and other wild animals lurking in the dense forest.

“Many people died,” Pierre says. “But we had to go on because otherwise, we’d die too. Whenever my son thinks about it, he cries.”

This video was taken by other Haitian migrants while crossing the Darien Gap.

Smuggled across Nicaraguan border

After 15 days in Panama and a bus ride to Costa Rica, authorities stopped them at the Nicaraguan border.

“It was really tough to get across,” says Pierre.

“We had no papers.”

Stuck at the border and living in tents, Pierre paid smugglers nearly $3,000 US to get him and his family into Nicaragua.

Others were not so lucky.

“Some were ripped off and never did get across,” he says. “There were many bandits who raped people when they were going through the forests.”

Once in Nicaragua those that made it took a bus through Honduras and Guatemala to Mexico.

Pierre says Mexican authorities gave them passage on the condition they move on to the USA.

But arriving at the American border in Tijuana, Pierre was detained and spent nine days in lockup.

Upon release, he moved his family to Florida.

Taste of the American dream

Pierre got a work permit while his U.S. asylum claim was processed, working as a check-in manager at the Orlando airport and at Disney World.

“I worked and waited for the [asylum] process to run its course,” Pierre says. “But when Donald Trump came to power things got complicated.”

He was worried that without permanent status, he and his family could be deported at any time.

Then Prime Minister Justin Trudeau tweeted his support for refugees during Trump’s efforts to enact a travel ban from Muslim-majority countries, and Pierre turned his eyes northward.

To those fleeing persecution, terror & war, Canadians will welcome you, regardless of your faith. Diversity is our strength #WelcomeToCanada

— @JustinTrudeau

“When [Trudeau] said, ‘Canada’s ready to welcome refugees,’ I said, ‘Well, if that’s the case, I’ll come to Canada,’ because I’m looking for a better life.”

So the family flew to Plattsburgh, N.Y., and boarded a bus to the border, crossing into Canada illegally at Roxham Road and making an asylum claim.

“When [Trudeau] said, ‘Canada’s ready to welcome refugees,’ I said, ‘Well, if that’s the case, I’ll come to Canada,’ because I’m looking for a better life.”- Haitian asylum seeker Pierre, 29

They spent 24 hours in a temporary camp near the border, then two weeks living in the shelter set up at Montreal’s Olympic Stadium.

The family now has an apartment, and Pierre is trying to get a work permit while he awaits his Immigration and Refugee Board hearing.

Accusations, beatings and stabbings back home

In his asylum claim, Pierre says he can’t go back to Haiti because his family is being targeted by a gang of street criminals.

He says the trouble started in 2009 when a woman in his neighbourhood accused his father of witchcraft and threatened to have a gang attack him with machetes.

Pierre says his father fled but the gang beat up his mother. He has copies of statements to the local police to help prove his story and a picture of his mother after the beating.

He claims the same group of thugs attacked him for his political views in 2010 on a visit home, accusing him of trying to organize an uprising against the government.

Then just this year, Pierre says his brother was stabbed by the gang and had to move his family to another part of the country.

“It’s a country with no justice,” Pierre says. “If I go back there they’ll kill me.”

‘Such a cruel journey’

Sitting in a coffee shop near Jarry Park in Montreal’s Villeray neighbourhood, Pierre sketches out a drawing of his long journey on the back of one the myriad documents and forms that make up his refugee case file.

The map fills the page. His home country is conspicuously absent.

Pierre sketches his journey from Brazil to Roxham Road.

“We left the U.S. because we were scared they’d deport us to Haiti,” he says.

“In Haiti most people are unemployed. It’s miserable. There are kidnappings all the time.”

Pierre hopes the Canadian government will give extra consideration to those like him who have come so far.

“Such a cruel journey,” he says. “It was a very hard road to get here.”

By: Simon Nakonechny | September 26, 2017

![Phyllisia Ross – KONSA [Official Music Video]](https://haitiville.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/phyliisia.jpg)