Arroz con pollo waits on the table at Miguel Sano’s duplex condo, not far from Target Field. Sano’s sister is visiting from the Dominican Republic, and her husband has made the Twins slugger’s favorite dish — mounds of it, enough to feed a baseball team. “Don’t worry,” Sano tells me. “I eat a lot.” The aroma is seductive, an anamnesis of the Caribbean. It fills the top floor of the apartment where Sano spends the major league season, more than 2,000 miles from San Pedro de Macoris, where he was raised. The coastal city is renowned for turning out big league talent, an important source for the country’s baseball pipeline — 82 Dominicans made last year’s Opening Day rosters from a population of 10.6 million.

Sano stands apart from the other 81 Dominicans in one significant way: He has publicly identified as an ethnic Haitian.

Baseball is not popular in Haiti itself, but as many as a million ethnic Haitians live in the neighboring Dominican Republic, where the game is ubiquitous. As the chicken waits on the table, Sano and Franklin Johnson Mateo, who serves as Sano’s adviser and facilitator, shout out examples of former and current MLB players who likely share their Haitian ancestry. They rattle off seven or eight names. The total number, Sano and Mateo agree, would shock most observers.

Many big leaguers from the Dominican, including some who are being mentioned in Sano’s living room, choose to keep their backgrounds a secret. Some ethnic Haitians go so far as to actually alter their identities on the way to the majors.

“I didn’t have to change my name, but there are so many that do,” Felix Pie, a former big league outfielder and Haitian Dominican, had told me.

Players need birth certificates to sign with a major league team and obtain a visa. Haitians in the Dominican Republic often lack them, so a player might change his identity to get the necessary documentation. Others do it to make themselves appear younger, or simply to avoid the rampant prejudice against Haitians in the country. “Dominicans make fun of Haitians,” Mateo says. “Some people feel ashamed about being Haitian.”

The Caribbean’s second-largest island, Hispaniola, is divided in two: French- and Creole-speaking Haiti to the west, the Spanish-speaking Dominican Republic to the east. For generations, Haitians, mostly descended from African slaves, have been denigrated by lighter-skinned Dominicans descended from colonial Europeans. The Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo, who used makeup to whiten his own face, murdered an estimated 20,000 émigrés during a 1937 massacre. Recent administrations have favored deportations.

The situation has lately become a human rights crisis. In 2013, a court ruling retroactively stripped some 200,000 Haitian Dominicans of their citizenship, even if they were born in the country. Those born there today are considered aliens. Tens of thousands have been deported or driven from the country by fear. Generations of Dominicans with Haitian blood are at risk. “I have a lot of friends who are scared that the government is going to send them back to Haiti,” shortstop Orlando Calixte told me in November. A Haitian Dominican, he signed with the Giants this winter after seven seasons in the Royals’ minor league system.

Until recently, changing an identity was easy enough to do. “If you were Haitian, you could go back and get papers from somebody,” Mateo says. “‘This is my mom and dad, I’m Dominican.’ But really it’s a fake mom and dad.” Mateo himself used an assumed name to play for several years in the A’s organization, though he won’t say what it was. Somewhere on the island, there’s a man with that name who has a minor league entry on the Baseball Reference website and probably a few thousand dollars for his trouble.

And Sano? His birth certificate reads “Miguel Jean,” as does his listing on MLB’s official Twins roster. But he goes by Sano, and that’s what it says on his jersey. When we finally sit down to lunch, Sano explains why his names don’t match. The story is murky, and he tells it quickly, without much detail. His mother, Melania Jean, was born in San Pedro de Macoris to legally settled Haitian parents. His father, who had the name Aponte, would come and go. So Melania put her last name on her son’s birth certificate.

Later, a man named Sano started living with the family. As the young ballplayer’s talent grew, that name became identified with him. “They’d call out to me in the street, ‘Sano, Sano,'” he says. He shrugs. “So that’s the name I started using.” Now that he’s famous, Sano takes pride in his ancestry, though he has never seen Haiti and can’t speak more than a few words of Creole. He denies that he changed his name to help his career, but when he was a teenage prospect in the Dominican Republic, it certainly wouldn’t have hurt.

Sano was lucky. When he was born, his mother insisted that the hospital provide papers. He still had to spend months fighting with Major League Baseball over their legitimacy, but in the end, they were enough. In 2009, he signed with the Twins.

But since then, a Haitian Dominican’s journey from talented adolescent to big leaguer has become increasingly difficult. In fact, young Haitians these days have trouble even finding a place on competitive Dominican youth teams. “Long before you get to Major League Baseball, there’s a selection process that discriminates against Haitians,” says Sandy Alderson, who worked for MLB in the Dominican and now serves as GM of the Mets.

Whatever he calls himself, the next Miguel Sano is far less likely to ever get off the island.

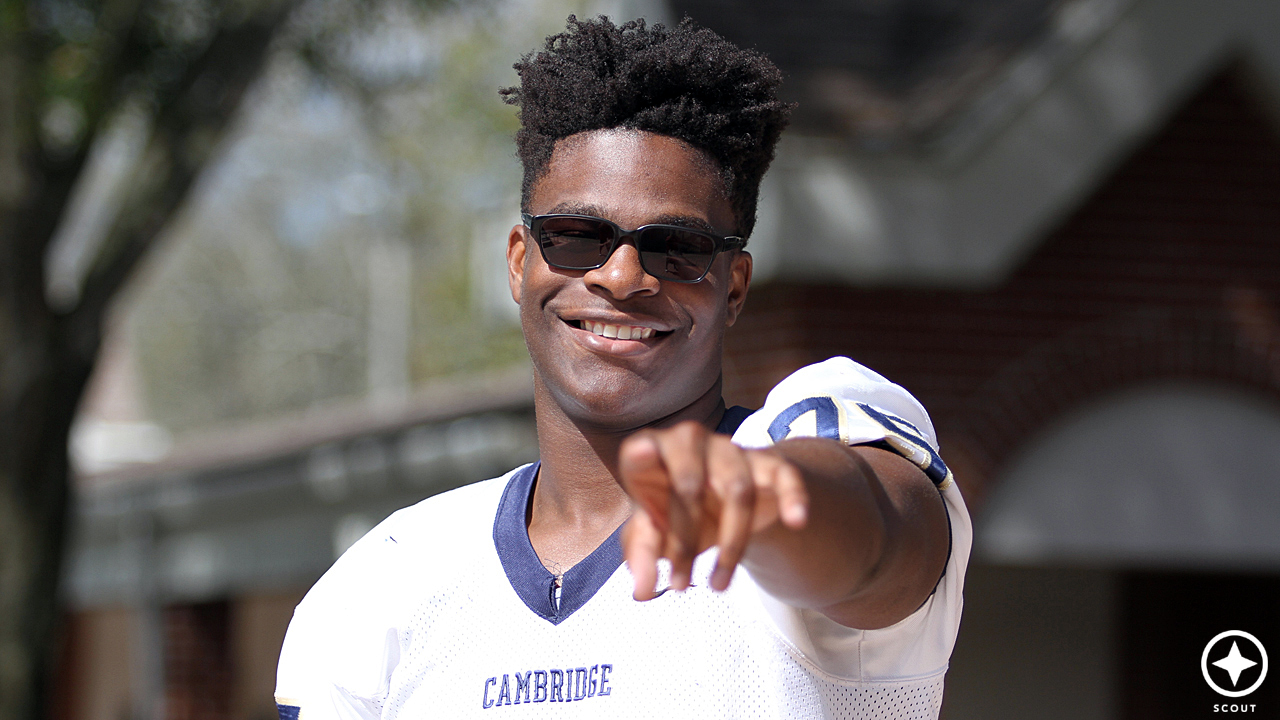

Miguel Sano (right) is one of the few players to embrace his Haitian roots. JESSE JOHNSON/USA

AFTER THE 2016 season, I flew to the Dominican Republic to try to understand why some of the most talented baseball players anywhere don’t play in the majors. I’d heard that Onil Joseph, a Haitian Dominican who works as an instructor at the Royals’ complex near Boca Chica, had a brother who was good enough. But nobody in baseball had seen him in years.

On a November afternoon, Joseph and I rumble over the packed dirt in his SUV, headed for the village of Angelina. The one-lane road is framed by walls of sugarcane. Though it’s only a 15-minute drive from the chaotic bustle of San Pedro de Macoris, it feels like a different country. It might as well be. The shantytown where Joseph was born and raised is half Haitian, he guesses.

Life is hard in Haiti. Even before the damage done by a devastating earthquake in 2010 and last year’s Hurricane Matthew, which killed more than 1,000 people and left cholera in its wake, mere subsistence was difficult for many to sustain. In North America, we perceive the Dominican Republic to be poor — and indeed, 32 percent of Dominicans live in poverty. But in Haiti, the poorest country in the Americas, that number is near 60 percent. For decades, Haitians have crossed Hispaniola’s porous border in search of fertile fields, decent employment, a better life. To them, the Dominican represents a promised land.

Many Haitian Dominicans live in shantytowns like Angelina, called bateyes, near the cane fields. Rico Carty, a lifetime .299 hitter who signed with the Milwaukee Braves in 1959, emerged from a batey. Plenty more players, including George Bell, Mariano Duncan and Julio Franco, have followed. Many of them, it must be assumed, have Haitian lineage.

Decades of oppression have pushed this Haitian subculture into the margins of society. Children are often born at home, with no government representative to record their existence. Hospitals can be far away — and expensive. And for Haitians, there is risk in being exposed to an official system that already has deported thousands of longtime residents. Sometimes the church gets involved, jotting down rudimentary details of a childbirth or a baptism, usually in French. “It’s just the way it happens here,” Joseph explains.

One MLB executive told me the story of a contract offer his team recently made to a young Haitian Dominican. The player had a birth certificate that seemed legitimate, except that it wasn’t issued until he was 10 years old. “In the U.S., you can’t leave a hospital without registering your child,” the executive said. “That’s not the case down there.” It also happened that, for unexplained reasons, the 10-year-old had been registered as the son of his aunt. That left him unable to pass a DNA test, when matched against the genes of his alleged parents. “He’s a talented player,” the executive said. “We’re trying to figure out what to do.”

Joseph’s SUV bounces to a stop, and he jumps out to show me where he and plenty of others learned to play baseball. It’s a rock-strewn dirt infield with a stretch of tall grass beyond. If you can field a grounder here, it seems to me, you can field one anywhere.

Onil Joseph works as an instructor at the Royals’ complex in the Dominican Republic. BENEDICT EVANS FOR ESPN

According to MLB rules, Dominican prospects are free agents, not subject to an entry draft. They can sign with teams any time after their 16th birthday. Notoriously, many prospects lie about their age, as Mateo did: Younger players are more valuable, and an 18-year-old posing as 16 will look more impressive to scouts. Fraud is a legitimate problem. But fraudulent documents can also serve as the only lifeline to players born without a birth certificate.

When Joseph signed with the Braves in 2000, he showed papers from somewhere. They were enough. He spent five years in the Atlanta farm system, then one with the Royals. Most of that was in Double-A or below, but it earned him enough to get food, clothes and medicine back to Angelina.

Now he drives down the village’s only street. It has rained, and pools of standing water glisten in the sunshine. The smell of something burning is in the air. People of all ages are sitting in front of the shacks on folding chairs. The idea that their birth certificates are filed away somewhere inside is a fantastical one.

Onil was playing in Wichita in 2007 when his brother signed a contract with the Giants that included a $350,000 bonus. That wasn’t close to the $3.15 million that Sano would get from the Twins two years later, but it was large enough to rank among the 20 biggest international signing bonuses of that season. When we arrive, Angel Joseph fills the doorway of his family’s two-room shack. Now 27, he is 6-foot-2 and a muscular 170 pounds. Beside him on the bare wall is a carving of a mermaid. “I was a complete ballplayer,” he says quietly. “I hit well. I ran well. I played center field.”

At the time, Angel was being compared with Alfonso Soriano. A switch-hitter, he had power from the right side and a graceful swing from the left. “Of all the outfielders we saw, he was one of the top three as far as having well-rounded tools,” Rick Ragazzo, who then ran the Giants’ international scouting division, said after the signing.

But unlike his brother, Angel Joseph didn’t have a birth certificate. There was no reason one brother had it and one didn’t, other than happenstance — who happened to be passing through that morning, perhaps, or how aggressive the parents had been in filling out a form. “I basically didn’t have any documents,” Angel says. “None. We looked and looked for a way to find them, but they weren’t there. It isn’t that they were missing, I never had them.”

Ultimately, his contract with the Giants was annulled. As he tells the story now, Angel grows silent. Onil picks up the thread. “He kept playing for the talent scouts,” he says. “He waited for years to have another opportunity. He kept saying he believed it would work out. He could play.”

Several years later, an Indians scout offered a contract. Because Angel was older and hadn’t improved as he might have with professional coaching and competition, the offer was $100,000. Again, he was asked to prove his identity. With the money Onil had earned, the family hired a lawyer. “It didn’t help,” Onil says.

Angel was in his early 20s by then. “I kept playing, kept trying,” he says. A Rays scout approached and said he believed he could solve the problem. They had a lawyer on retainer, he boasted, for exactly that circumstance. “He came down to see me, tried to get me a visa,” Angel says. But that failed too.

Angel lives in the shack with five other family members. He is the pastor of a local church and, as he approaches 30, resembles Lorenzo Cain. But he isn’t a center fielder anymore. “I’ve stopped playing,” he says. “I’ve lost the ambition. My life is different.” He stares out at the dirt road. “Sure, I could have played in the majors,” he says. “They compared me to Felix Pie.”

Both brothers are silent now as thunder rumbles overhead. A woman yells something in Creole to two kids playing in the street. Angel lowers his head to lean out from the undersized doorway and looks up at the sky. The rain is coming again.

AT THE TIME that the Joseph brothers were trying to get off the island, each team had its own way of verifying the identities of the players it wanted to sign. The U.S. government had tightened visa restrictions after the 9/11 terrorist attacks in 2001, so some form of valid identification became more important. But players could still slide through, especially if they were good enough. “Something needed to be done,” says Kim Ng, MLB’s senior vice president who is responsible for international affairs.

As Onil drives me back to San Pedro de Macoris, where I’m headed to see a Dominican winter league game that night, I can’t help thinking that I could be going to watch his brother play. Instead, we’re planning to meet another player Onil knows, Calixte. The former Royals farmhand joined the Estrellas Orientales winter league team earlier in the week. His story is similar to Angel’s. But after a mysterious trip to Haiti made by his father, it turned in the other direction.

We pull up to the stadium, which is painted a tidy green and white. The sky shows clouds pierced by shafts of light. The stadium is small, like something out of the Texas League, except with pork and rice at the concession stand. A steady thwack emanates from a batting cage down the first-base line. That’s Calixte, trying to get up to speed with extra hitting.

When Calixte signed a contract with Kansas City in 2010, the path to the major leagues was narrowing for Haitians. He made it out, but barely. Now 25, he played at Triple-A Omaha and Double-A Northwest Arkansas last season. On Nov. 7, he was granted his free agency. Four days later, he signed a minor league contract with the Giants. He is likely to spend this season in the major leagues, a Giants executive says. On this night, he looks the part, rapping out four hits.

The next day, he pulls up to a shopping mall in his hometown of Santo Domingo. He’s driving a white Toyota 4Runner, the only gift he bought for himself when he signed with the Royals. As we drive, he tells me what it means to be a Haitian in a country that is at once utterly familiar and entirely strange. He was born and raised in the heart of the city, yet he has a Haitian passport and a Dominican identity card that identifies him as a Haitian citizen. “Nobody says anything to me because I speak Spanish,” he says. “But a lot of the Haitians here don’t. There’s prejudice against them. That’s why players don’t want to come out and say ‘I’m Haitian,’ even if they were born here and their parents were born here. They don’t want to have to deal with all that.”

Calixte’s father, Dieudonne, crossed legally into the Dominican Republic in 1977. Once there, he stayed and had several sons. At one point, one of them tried to play professional baseball. He was 18 but knew he’d have a better chance if he were younger. So he adopted the identity of his little brother, Orlando, who was 15.

If that faux Orlando Calixte had been good enough, the ruse would have worked. He wasn’t. But the little brother, the one who’d been born Orlando Pierre Paul Calixte on Feb. 3, 1992, was better: a line-drive hitter and dependable shortstop with a great arm. The Red Sox planned to offer him a contract when he turned 16 early in 2008. One principal involved remembers the figure as $3 million. Another says it was $2 million. “But I had a problem,” Calixte says.

Before the Red Sox would sign him, they wanted to investigate. “They have to make sure it’s my real name, my real age,” he says. “That everything I’m saying is correct.” In Calixte’s case, it wasn’t. “I put my name as Wilson Calixte,” he says, “because my brother had already used Orlando.” The Red Sox didn’t understand the reason behind the discrepancy or why a family might have two sons and name them both Orlando, but they sensed trouble. They withdrew the offer.

Stunned, Calixte admitted to MLB that his brother had lied. He went to get his birth certificate as proof but discovered that the local government wouldn’t provide it. “They told me, ‘We can’t give you one because both your mother and your father are from Haiti,'” he says. More than a year passed with Calixte in limbo.

The Royals had scouted Calixte. They believed his story. More important, perhaps, they liked his bat and the way he handled himself at shortstop. They envisioned him playing in Kansas City. But he needed that piece of paper, that proof of his existence, to get him there.

“I’ve stopped playing. I’ve lost the ambition,” Angel Joseph says. “Sure, I could have played in the majors. They compared me to Felix Pie.” BENEDICT EVANS FOR ESPN

Calixte had just turned 18 when the Royals offered $1.3 million in early 2010, provided he could produce a birth certificate. Months passed. Eventually, he says, his father drove from Santo Domingo to Port-au-Prince, the Haitian capital. When I met Dieudonne Calixte, he told me a story that involved clerks and offices and meetings and research and left me understanding less than when he’d started. Somehow, though, he returned with a document. His son got his deal but at a lower price. “We’d agreed to a number,” says Rene Francisco, who runs the Royals’ international operations. “But we ended up giving him a little bit less because it went on for so long.”

That August, Calixte officially signed with the Royals for $1 million. Those few months of enforced idleness cost him $300,000. The two previous years had cost him as much as $2 million more. “My brother apologized,” he says now.

Any more delay might have been disastrous. Calixte’s signing came just as MLB was starting to enact a new policy for verifying identities. Commissioner Bud Selig had appointed a committee to research solutions to the rampant age fraud, and one of its main recommendations was that the league establish a far stronger presence on the island. Sandy Alderson, who’d been running the Padres but left in 2009 when the franchise was sold, had chaired the committee. He agreed to lead the new effort.

The Harvard Law grad and career baseball man arrived in the Dominican in early 2010 and stayed for about 10 months before becoming the Mets’ GM. He set in motion practices that, though controversial for their invasiveness, have gone a long way toward eliminating fraud. Top prospects were forced to register with MLB and agree to an age and identity investigation. If the investigation came back inconclusive, the next step could be a DNA test to confirm parentage. “What was widespread fraud in 2010 has become far less,” Alderson says.

But that, he acknowledges, has come at a price for Haitian Dominicans. “I wouldn’t say that intended consequences were to leave a specific group of people outside the benefits of that process,” he says. “But in essence that’s what has happened.”

Few of the buscones, coach/agents who prepare talented Dominican teenagers to be seen by scouts, will now take chances on kids with little hope of getting a contract validated, let alone a U.S. visa. “Everybody here has sympathy for the issue,” says Ng, the MLB senior VP. “For the Haitians, it’s just happening earlier than for anyone else because they’re known as not being able to get documentation.”

MLB has no plans to address the problem.

If Puason makes it, Ozuna will earn a percentage of his contract. BENEDICT EVANS FOR ESPN

AFTER SPENDING ALMOST a week on the island, it is clear to me that MLB policy has combined with the Dominican government’s recent suppression to create a nearly impossible situation.

In 2013, the Constitutional Court of the Dominican Republic ruled that children born to undocumented parents in the country since 1929 — the year Haiti and the Dominican Republic formalized their border — never had been entitled to citizenship. The government set a deadline of June 17, 2015, for these newly categorized aliens to leave on their own or register with authorities. When that date passed, the government began mass deportations. Amnesty International has reported the existence of spot checks on city streets. There have been reports of violence, even lynchings. In addition to the tens of thousands who have been deported — nobody knows exactly how many — thousands have fled on their own.

With so much upheaval, baseball might seem like an afterthought. Still, the game offers rare economic hope for Haitian Dominicans. Since the 2013 ruling, there is even more fear of registering with authorities. Documentation has also become harder to obtain.

There is an irony to this: Baseball was introduced to the Dominican Republic in the late 19th century by Cuban laborers who had fled war at home to come harvest sugarcane, as Haitians do now. Gradually, baseball became part of the culture. Now it serves to define the country perhaps more than any other aspect of Dominican life.

With a couple of days left in the country, I head into Boca Chica, about halfway between Santo Domingo and San Pedro de Macoris, to meet the buscon, JD Ozuna. He is one of the few still willing to take a chance on Haitians. I find him sitting inside his mother’s law office, Guzman Peña & Asociados, shaking his head at the lousy weather. The two-story stucco building is located directly behind home plate of the baseball field where Ozuna runs his own academy. Out the open door of the office is a wire backstop, a dirt infield and grass gone to weeds in the outfield.

Ozuna makes his living training players who have a chance to sign with a big league organization. The word “buscon” is a neologism, formed from the Spanish verb buscar, meaning “to look for.” Ozuna will get a tip from a coach about a young player. Perhaps he’ll offer a spot. If so, the coach will expect a payment.

Ozuna will provide equipment, training and competition until the player is eligible to be signed. In return, he’ll get a hefty cut of the first contract. Most buscones won’t deal with Haitians anymore, but Ozuna has a strong sense of social justice. He believes talent is talent. “I remember Sano,” he says.

But he’s careful. The stakes are high. If you don’t have a birth certificate, there’s nothing he can do. “The first questions are always, ‘How old are you?’ and ‘Do you have documents?'” he says. “In many cases, a player will use a false name. So we open our own investigation to make sure that the name is real.”

Ozuna tells me that a little more than a year ago he became aware of “the next great Dominican superstar”: a 12-year-old with unusual skills living in La Romana, down the coast from San Pedro de Macoris. A coach brought the young shortstop to him, Ozuna says, wanting a small percentage of his first contract. The player’s name was Robert Puason, and he happened to have Haitian roots.

Ozuna watched Puason play and couldn’t believe what he was seeing. Before he let himself get excited, he hired an investigator. “It took 30 days,” he says. “We learned that Puason is Puason. He has documents, gracias a dios. All perfect.”

La Romana is best known in the United States for the Casa de Campo resort. Puason’s family’s neighborhood was at the far end of the spectrum from such luxury. His house had no walls and an earthen floor. “It’s called a casa de sin,” Ozuna says, “sin” meaning “without” in Spanish. “Four, five brothers and sisters living together.”

Soon after he started with Ozuna, Puason became morose. He’d been a happy kid, with a goofy smile. Now he shuffled through workouts like a robot. When Ozuna inquired, Puason confessed that he was worried. “My family isn’t eating,” Puason told him. “My family went two days and only ate once.” Ozuna considered the money he’d already paid for Puason, weighed it against his potential and decided to spend more. “He’s a ballplayer who is very, very special,” he says. He gave Puason’s family money for food. Then he moved them into a better house. He brought Puason to live with him in Boca Chica.

The following morning, my last in the country, I come back to meet Puason. At 14, he is 6-3 and wiry. He hits the ball with ferocity. When Puason was 10, Ozuna notes, he was already playing alongside former pro players in an open men’s league in the Dominican countryside. “He was a boy, and they put him in right field, but OK, he played,” he says. “And he wasn’t scared. Pitchers throwing 95, 96. And he learned to hit that kind of pitching.” Asked how much Puason has progressed since he started teaching him, Ozuna laughs. “We didn’t teach him anything,” he says.

Ozuna believes Puason already has the size and skills of Sano at 16. “If the system allowed it, they’d sign him right now,” Ozuna says. “There are three or four teams that would give him $4 million, $6 million. But the rules don’t permit it. So you have to keep working to keep the value up.”

Ozuna leaves to pick up Puason at school. By the time they return, raindrops are drumming on the concrete. Pools of water have formed in the infield. Puason seems devastated. He’s clearly still a child, with a high voice that cracks when he gets excited. Baseball is his passion, he tells me. His favorite player is Bryce Harper, so he likes the Nationals. But his dream is just to play in the majors. When I ask him which teams he has spoken to, he answers shyly, “Almost all of them.”

But no matter how good he is at 14, no matter how much the scouts like him, nothing about Puason’s future is secure. “He has papers,” Ozuna insists. But Sano had papers too, and getting his contract validated was still a drawn-out and precarious process. And that was before the MLB crackdown.

Even when you think you’re sure, Ozuna admits, you can never be sure. Not until organized baseball makes its ruling, after conducting its investigation. And during that process, the burden of proof is on the player to validate his existence. “You have to present a record,” the Royals’ Francisco explains. “Present a case that you are that person. And hope that baseball accepts it.”

Millions of dollars for the buscon and the teenager might depend on how assiduous some civic functionary was at recording Puason’s birth. If this were almost anywhere else in the baseball-playing world, he would control his destiny. Not here. Not as a Haitian.

Ozuna makes a gesture like tossing a ball in the air, as if to say that the situation is out of their hands. All they can do, he tells me, is wait.

by Bruce Schoenfeld – ESPN 03/14/17

![Phyllisia Ross – KONSA [Official Music Video]](https://haitiville.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/phyliisia.jpg)